Virtual Boy Reborn: How Nintendo's Switch Add-On Redeems a Historic Flop

Editor's Note: This article explores a detailed hypothetical scenario for a Virtual Boy revival, based on a conceptual plan. It is an analytical piece examining how such a move could recontextualize...

Editor's Note: This article explores a detailed hypothetical scenario for a Virtual Boy revival, based on a conceptual plan. It is an analytical piece examining how such a move could recontextualize a notorious failure, not a report on confirmed products.

The mere concept of a physical Virtual Boy accessory for the Nintendo Switch sends a unique tremor through the gaming imagination. It’s not the shock of a new console, but the profound surprise of a ghost returning—not for vengeance, but for vindication. For a generation raised on tales of Nintendo's infallibility, the Virtual Boy stands as its most notorious commercial misstep: a monochrome, headache-inducing console relegated to the darkest corner of gaming history. A hypothetical 2026 revival as a Switch peripheral forces a compelling re-evaluation. This isn't mere nostalgia bait. It's an opportunity to ask: could a new generation, armed with modern hardware, finally discover that the ideas behind Nintendo's biggest disaster weren't all bad?

From Flop to Function: A Virtual Boy Reimagined

In this speculative scenario, the new Virtual Boy accessory represents a fundamental reimagining of the original concept. It is not a console, but a peripheral—a required one for accessing a dedicated Virtual Boy library on a service like Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack. This distinction is everything.

The strategic shift is profound. Nintendo would not be asking players to invest in a risky, standalone platform as it did in 1995. Instead, it would offer an optional, novel window into its archive for the established, massive install base of the Switch. It transforms a failed product into a curated experience, mitigating the original's physical and financial pain points from the outset.

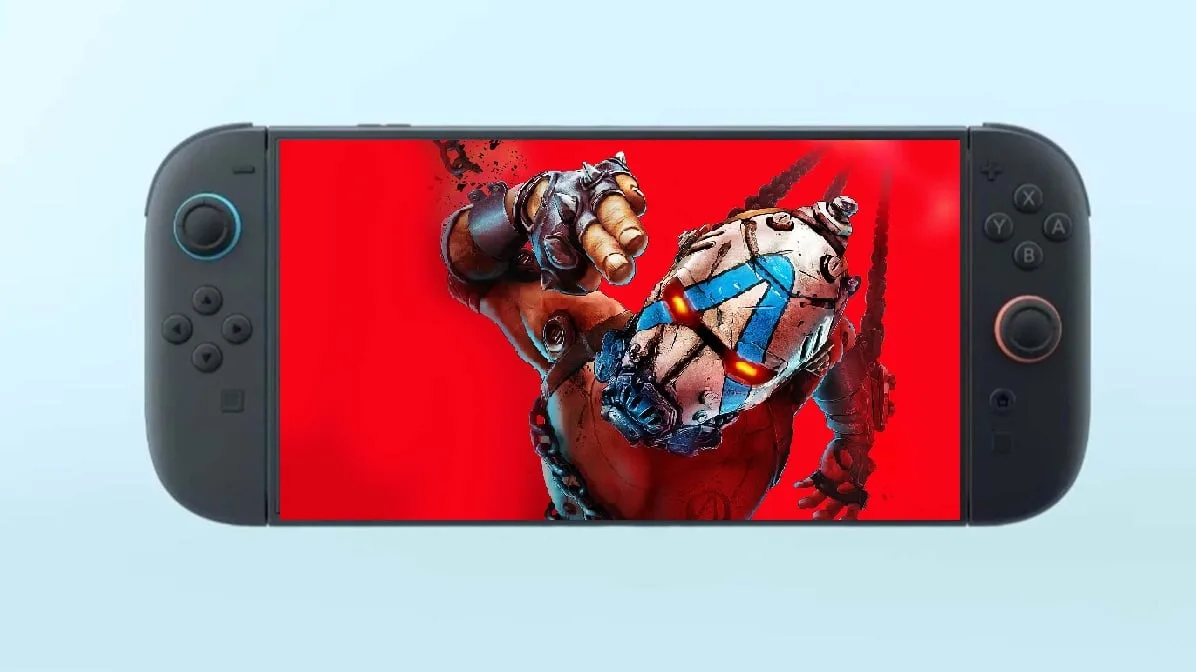

The accessory itself, as conceptualized, is a clever piece of hardware recontextualization. For a hypothetical $100 (or a DIY-friendly $25 cardboard version), it would function primarily as an elaborate housing with specialized lenses and a red filter. It would use the Switch's own high-resolution screen to create a stereoscopic 3D effect, replicating the iconic red-and-black visual signature of the 1995 original. Crucially, it would address the foundational flaws that doomed its predecessor. A modern design would incorporate cushioned sides for comfort, eliminate the need for a bulky tabletop stand by working with the Switch's portability, and sidestep the original's dim, single-color active-matrix displays entirely.

The Virtual Boy's Buried Legacy: Good Ideas, Bad Execution

To appreciate a potential revival, one must honestly confront the original's failure. By any standard metric, the Virtual Boy was a disaster. It was discontinued in less than a year, having sold fewer than 800,000 units worldwide against a target of millions. Its library was anemic, capped at just 22 official releases, leaving players with scant justification for the purchase. Most damningly, its hardware—with a stationary, eyestrain-inducing viewfinder and a monochrome red display—delivered a physically uncomfortable experience that became its defining memory.

However, to write it off as a total creative void is to miss its buried legacy. The Virtual Boy was a bold, early foray into stereoscopic 3D and immersive, "in-the-machine" gameplay a decade before the 3DS. Its unique hardware spurred novel control schemes, most famously the dual D-pads of Teleroboxer for simulating left and right fist controls. It was an attempt to create a deeply personal, visually distinct gaming experience. Its commercial crater likely served as a harsh but invaluable lesson for Nintendo, teaching a balance between wild innovation and calculated market readiness—a tension that has defined the company's biggest swings, from the Wii to the Switch, ever since.

A Second Chance for a Lost Library

In this concept, the accessory's true purpose is to serve as a key to a vault. A service like Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack could launch with a curated lineup of seven Virtual Boy titles: Teleroboxer, Galactic Pinball, Red Alarm, Golf, the acclaimed Virtual Boy Wario Land, 3D Tetris, and The Mansion of Innsmouth. This would be more than preservation; it would be strategic reintroduction.

The historical significance would deepen with the promise of more titles to come, including never-released games like Zero Racers and D-Hopper. For the first time, Nintendo could not just archive this era but complete it. The context is transformative. In 1995, these games had to justify a $180 console. In a modern hypothetical, they would be quirky, experimental entries in a vast subscription library. Virtual Boy Wario Land could be appreciated as a solid platformer, and Red Alarm as an ambitious early polygonal shooter, without the burden of propping up a failed system. Their novelty could finally be enjoyed as a feature, not a flaw.

The Bigger Picture: Nintendo's Strategy of Recontextualization

A Virtual Boy revival would not be an isolated nostalgia play. It fits within a coherent, forward-looking strategy evident in other hypothetical moves, such as a "Meetup in Bellabel Park" expansion for Super Mario Bros. Wonder on a next-gen system. Such a $20 upgrade would recontextualize a recent hit by adding enhanced visuals, new characters, areas, and massive new multiplayer and solo content.

Together, these conceptual moves reveal a potential master playbook: using new hardware and accessories to recontextualize and enhance software, both old and new. A new console and a Virtual Boy accessory would be frames that change how we perceive the art within. This strategy minimizes risk while maximizing the value of Nintendo's unparalleled IP and history. It could turn past commercial failures into fascinating service content and recent successes into evergreen platforms. It acknowledges that the value of an idea is not fixed at its launch but can be rediscovered and redeemed in the right context.

A hypothetical new Virtual Boy accessory would succeed precisely because it would not attempt to resurrect the failed 1995 console. Instead, it would perform a clever act of historical salvage, extracting the interesting ideas and unique games from the wreckage of flawed execution. By delivering them through a successful ecosystem, as an optional accessory for a subscription service, it would neutralize their original drawbacks. The headaches, the high cost of entry, the limited software—all would be gone. What would remain is a chance to experience a bold, strange chapter of gaming history on its own curious terms.

Ultimately, this hypothetical revival offers a blueprint for how the industry can honor its past: not by whitewashing failures, but by thoughtfully extracting their worthwhile ideas and making them accessible. It suggests that in the right context, even the most infamous flops can find their audience and contribute their unique verse to gaming's ongoing story.

Tags: Virtual Boy, Nintendo Switch, Nintendo History, Gaming Hardware, Nintendo Switch Online, Analysis