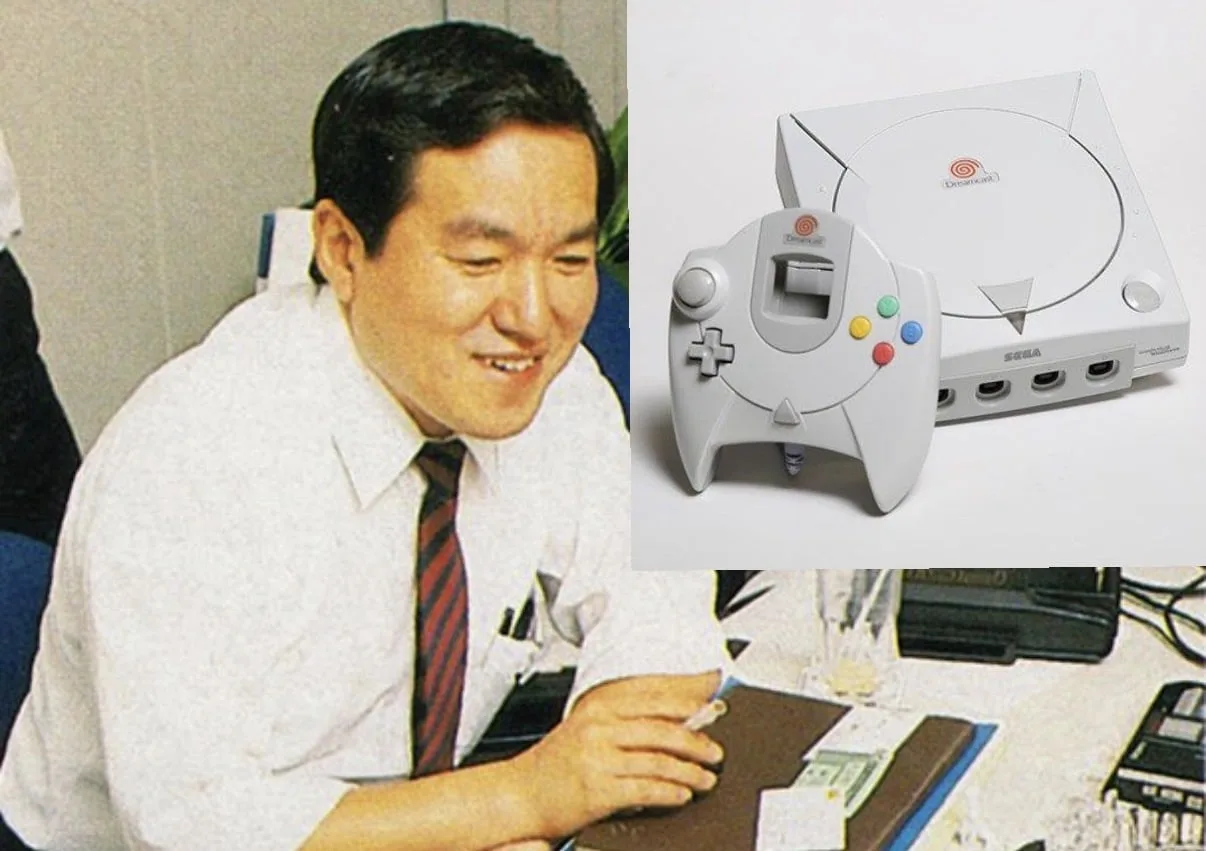

The Architect of Sega's Golden Age: Remembering Hideki Sato and His Console Legacy

From Arcades to Living Rooms: The Sato Design Philosophy Hideki Sato’s approach to console design was born in the glow of arcade cabinets. Upon joining Sega in 1971, he carried a core belief that...

From Arcades to Living Rooms: The Sato Design Philosophy

Hideki Sato’s approach to console design was born in the glow of arcade cabinets. Upon joining Sega in 1971, he carried a core belief that would define his career: home consoles should be "an extension of arcade technology." This was more than a marketing slogan; it was an engineering mandate. In an era where home gaming often meant compromised ports, Sato’s teams pursued the integration of cutting-edge arcade components into consumer hardware, a philosophy that set Sega apart from its competitors from the very beginning.

This vision was first realized in arcade hardware like the Sega System 1 board before making the leap to the living room. The SC-3000 home computer and its sibling, the SG-1000 console—Sega's first foray into the home market—laid the technical and philosophical foundation. They established the template: leverage Sega’s arcade prowess to deliver a distinct, power-focused experience to the home user, a thread that would run through every console bearing his imprint.

Engineering an Empire: The Genesis of a 16-Bit Champion

The purest expression of Sato’s arcade-first philosophy arrived with the Mega Drive, known in North America as the Genesis. Its development was directly linked to the rise of 16-bit CPUs in arcades. As Sega’s arcade divisions began adopting more powerful hardware, Sato’s R&D team initiated work on a home system that could serve as a true conduit for that experience.

A critical, strategic decision cemented the console's fate: the use of the Motorola 68000 processor. By the time the Genesis launched, the cost of this powerful chip had decreased significantly, allowing Sega to offer formidable 16-bit power at a competitive consumer price point. This technical pragmatism married to arcade ambition resulted in Sega's most commercially successful console. The Genesis became the hardware bedrock of the "Sega does what Nintendon't" era, enabling iconic titles that felt closer to their arcade counterparts and defining a generation of gaming rivalry.

The Final Dream: Pioneering the Online Future with the Dreamcast

If the Genesis was the pinnacle of bringing the arcade home, the Dreamcast was Sato’s visionary leap into the future. Its core concept shifted from pure power to "play and communication." This wasn't abstract; it was engineered into the machine's DNA through two pioneering hardware features: a built-in 56K modem and the interactive Visual Memory Unit (VMU).

The VMU was a memory card with an LCD screen and buttons, enabling portable mini-games and unique in-game interactions. The modem promised a connected gaming frontier. This ambition, however, came with a blend of marketing bravado and technical reality. While advertised as a "128-bit" system—a claim Sato later admitted was an exaggeration—the console was powered by a heavily customized and potent 64-bit Hitachi SH-4 CPU. The Dreamcast, Sega's final console, was a project of staggering innovation, tragically ahead of its commercial time but a direct reflection of Sato’s forward-looking design ethos.

The Lasting Impact: A Legacy Cast in Silicon

Hideki Sato’s influence extended far beyond Sega’s exit from the hardware business in 2001. Industry analysts consistently credit the Dreamcast’s integrated online infrastructure with directly paving the way for the standardized, console-centric services that followed, namely Xbox Live and PlayStation Network. The concept of a console as a connected communication device, which seemed novel in 1998, became an industry prerequisite.

Sato’s leadership was also crucial in navigating the aftermath of this innovative but commercially challenged project. He served as Sega's acting president from 2001 to 2003, steering the company through its critical transition to a third-party software publisher—a move that required the same pragmatic vision he applied to hardware. Upon his retirement in 2008, he left behind a legacy as a legendary hardware designer whose work defined the technological identity of a beloved competitor throughout its golden age.

The narrative arc of Hideki Sato’s career—from the arcade-inspired Genesis to the network-pioneering Dreamcast—charts a significant course in gaming history. His legacy is physically embedded in the circuitry of classic consoles and philosophically embedded in the industry's standards. While Sega ultimately exited the hardware arena, the core concepts Sato championed with relentless focus—raw power, bold innovation, and persistent connectivity—evolved from differentiating features into foundational expectations. Hideki Sato's true legacy, therefore, is not just in the consoles he built, but in the competitive, innovative, and connected spirit he engineered into the very heart of the video game industry.

Tags: Sega, Video Game History, Hideki Sato, Dreamcast, Genesis