Highguard's Turbulent Launch: How Online Backlash and "False Assumptions" Doomed an Indie FPS

“We were turned into a joke from minute one.” That stark reflection from Josh Sobel, former lead technical artist at Wildlight Entertainment, captures the brutal fate of Highguard . Just hours...

“We were turned into a joke from minute one.”

That stark reflection from Josh Sobel, former lead technical artist at Wildlight Entertainment, captures the brutal fate of Highguard. Just hours earlier, his team had experienced a career pinnacle: closing The Game Awards 2024 with the reveal of their ambitious, free-to-play FPS. Designed as a launchpad into the stratosphere, that coveted spotlight instead triggered a firestorm. The story of Highguard is a modern parable, demonstrating how a narrative, once cemented by the online gaming community, can dictate a project’s fate long before anyone presses ‘play’. It forces a critical question: in an era of instant, collective judgment, what power does pre-launch discourse truly wield over the future of independent studios?

From Show-Closer to Punchline: The Announcement Backlash

Internally, the mood at Wildlight was one of cautious optimism. Sobel has stated that pre-reveal feedback was “quite positive,” with the team confident they had a competitive, financially viable product. Securing the final slot at The Game Awards felt like a triumph. Yet, the trajectory shifted almost instantaneously.

The pivot point was a single “false assumption,” as Sobel describes it: widespread, unverified reports from prominent journalists that Wildlight had paid a staggering “million-dollar ad placement” fee for their closing slot. This narrative frame was catastrophic. It transformed Highguard from an ambitious indie project into a symbol of perceived corporate bloat and cynical marketing. The backlash was swift and severe. Announcement trailers were heavily downvoted. Comment sections flooded with dismissive memes, branding the game “Concord 2” or lamenting that “Titanfall 3 died for this.” A negative consensus was formed not on gameplay, but on the perception of the studio’s spending and intent. The game was tried and convicted in the court of public opinion before its code reached a public server.

Launch Into the Storm: Review Bombs and Layoffs

Highguard launched on January 26, 2026, into this pre-formed hurricane of negativity. Paradoxically, by traditional metrics, its debut was technically successful. It broke into the top 10 for weekly active users on Steam in the US and the top 20 on PlayStation and Xbox networks—a strong start for any new live-service title. However, this surface-level engagement masked a deeper rot.

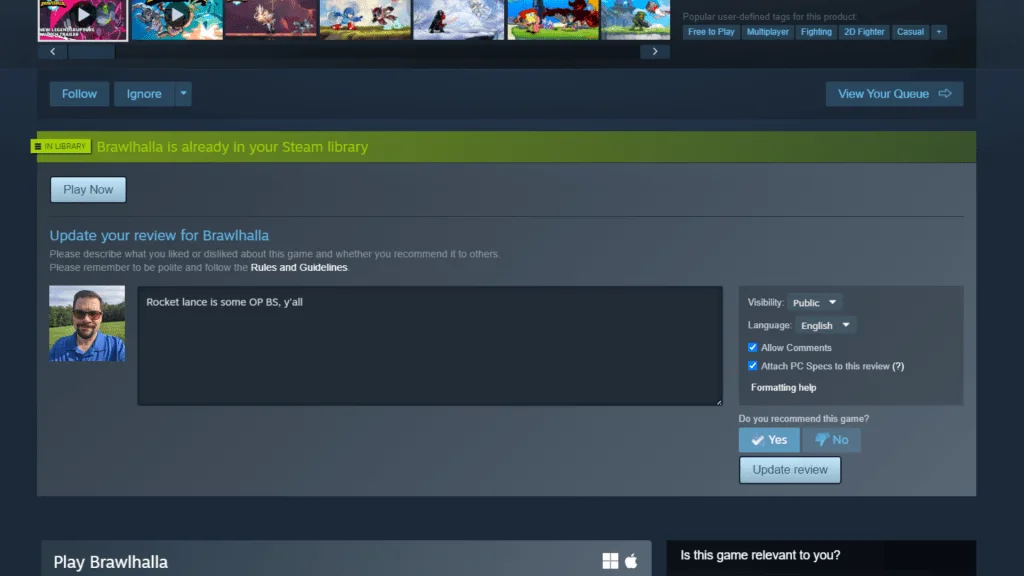

The game was immediately subjected to a coordinated review-bombing campaign. Sobel revealed it received over 14,000 negative reviews at launch from users with less than an hour of playtime, many of whom had not even completed the tutorial. This artificially cratered its public score, creating a powerful disincentive for new players. Legitimate criticisms did exist from those who played more substantially; feedback highlighted issues with map size and disappointment with the initial 3v3 team format. To its credit, Wildlight was responsive, rolling out patches and eventually making a 5v5 mode permanent.

But the damage was done. The momentum from launch had collapsed under the weight of the pre-existing narrative. In March 2026, less than a month post-launch, Wildlight Entertainment initiated layoffs impacting a majority of the development team. A core skeleton crew remains, but the dream of a thriving, developer-led live-service operation had been gutted in weeks.

The Developer's Perspective: Autonomy, Abuse, and Analysis

Amidst the data of review bombs and layoffs lies the human cost—a perspective best articulated by those who built the game. Josh Sobel’s account provides a crucial counterpoint to the online caricature. He emphasizes that Wildlight was the antithesis of the corporate entity it was accused of being: a truly independent, self-published, developer-led studio that explicitly did not use AI and operated without external corporate oversight. The irony is profound—a project criticized as a symbol of corporatization was actually a casualty of a backlash against perceived corporatization.

The personal cost was immense. Sobel describes receiving intense personal hate, including mockery targeted at his autism. This abuse highlights the dark underbelly of online mob mentality, where criticism of a product blurs into attacks on its creators.

His core analysis is clear: while not the sole factor, the consumer-driven online backlash “absolutely played a role” in the game’s struggles. “Consumers have a lot of power to influence the fate of a product,” Sobel argues, pointing to the direct line between the annihilated launch window narrative, the review bombs, the stalled player growth, and the subsequent business decision to lay off staff. In his view, the community’s collective voice didn’t just critique the game; it actively shaped its commercial reality.

Industry Rally and Broader Implications

Sobel’s story resonated powerfully within the development community. An unlikely coalition of studios rallied in support, publicly criticizing the knee-jerk internet hate. Developers from 1047 Games (Splitgate), Larian Studios (Baldur’s Gate 3), and Epic Games offered defenses, with industry veterans like Swen Vincke and Cliff Bleszinski speaking out. This solidarity underscores a shared anxiety among creators about the volatility of the modern launch environment.

Sobel’s broader concern extends beyond Highguard. He worries that such patterns of destructive backlash could have a chilling effect, driving innovative indie studios away from risky multiplayer projects and back “into the corporate industry” where they are seen as safer from such volatile public reception. The potential result is a stifling of creativity and a gaming landscape where only the largest, most risk-averse corporations dare to venture into certain genres.

Highguard’s journey is a potent cautionary tale for the contemporary gaming ecosystem. It illustrates the terrifying speed at which a narrative can be set in digital stone, often based on incomplete or incorrect information, and how that narrative can directly impact careers, creativity, and commercial viability. It exposes the tension between valid, constructive criticism and the destructive power of bandwagon hate.

Despite the emotional toll and the abrupt end to his work on the project, Sobel expresses no regret. He holds onto a note of cautious hope—for the small, dedicated community that enjoys Highguard, and for the remaining team striving to support it. His experience leaves us with a pivotal question: When a narrative formed in hours can dismantle a project built over years, where does informed criticism end and irrevocable harm begin? The fate of the next ambitious, independent “Highguard” may well depend on the answer.